Frankincense: Now and Then

In 1493 BC, the Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut organised a major trade mission outfitting five ships to journey to the Land of Punt. Often referred to as ‘the land of the gods’ it’s believed to be southern Arabia, present-day Somalia or Eritrea. As part of the mission, thirty-one frankincense trees were brought to Egypt. It was the first time the trees were successfully transplanted to another country where they grew happily for centuries.

The land where frankincense trees have traditionally flourished and where they abound to this day is in Oman’s southern province, Dhofar. For millennia, this quiet corner of earth supplied the civilised world with a key luxury item.

Frankincense is a resin, harvested from the Boswellia Sacra tree. When the trunk is slashed or wounded, a white resin oozes from the cut to heal the wound.

Since high school, history has always been my passion. The difference now is that I look for history in the every day.

Frankincense was such a valued commodity, (the story of the gifts brought to Jesus by the ‘three wise men’ is an example of its reputation) that its country of origin came to be known as Arabia Felix (Blessed Arabia) and the trade in incense created a series of global trade routes by sea and caravan.

Considering the Roman Emperor Nero once burned an entire year’s harvest of frankincense at the funeral of his favourite mistress Poppaea, the frankincense industry has slowed to a trickle today. But the trees are still grown, maintained and flourish in Dhofar.

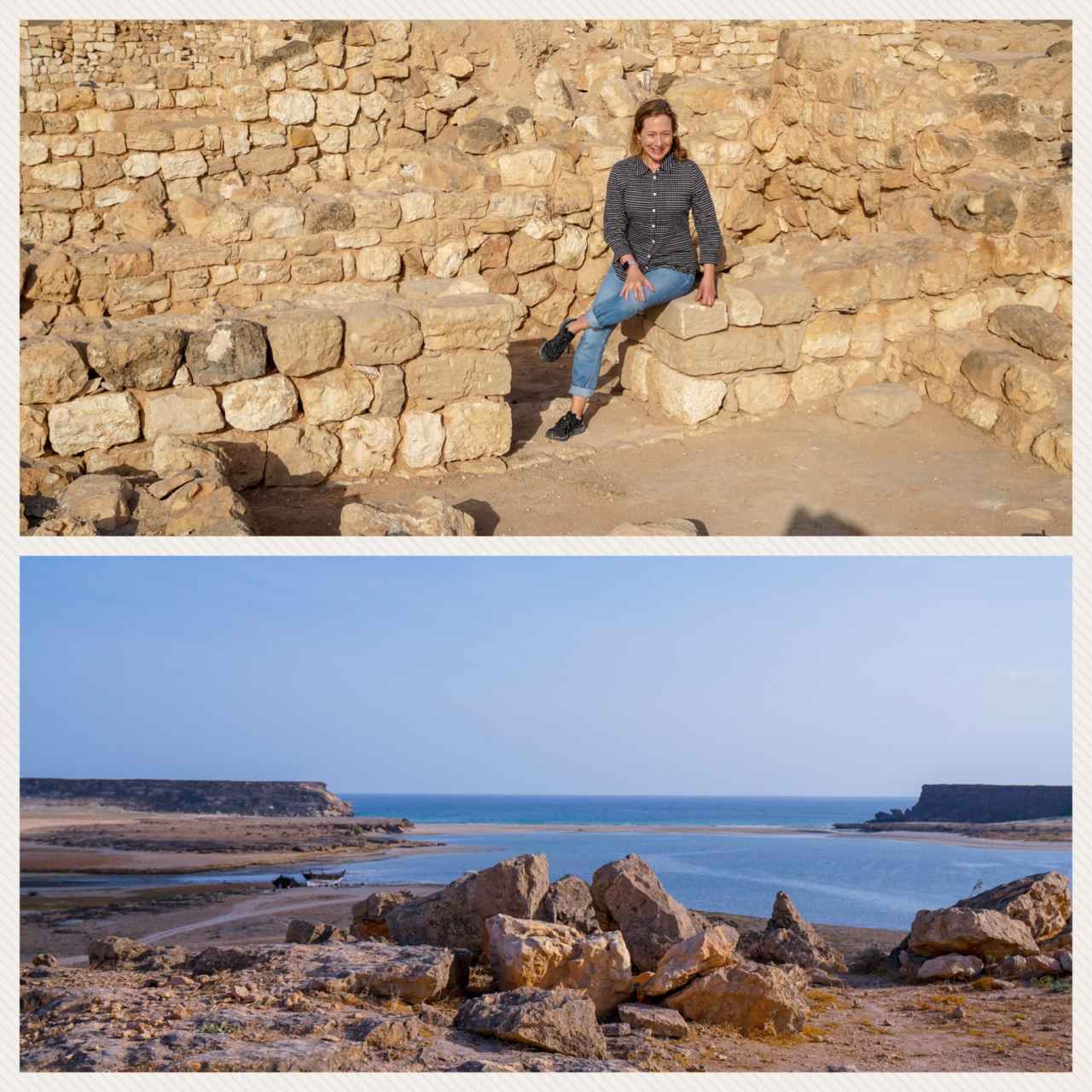

I recently took a group of travellers to Oman to see the main historical sites relating to the frankincense production and trade in ancient Arabia. We visited the archeological park of Sumhuram.

Established in the 3rd century BC, the port settlement – perched on a headland with its own natural harbour – existed for at least eight centuries. Apart from homes, kilns, temples, a burial complex and a mint, the city contained warehouses to store frankincense collected from inland regions, until the monsoon winds were favourable to carry the commodity to the markets of India.

In the frankincense alley of Muscat’s Muttrah Souk, I watched as a procession of families came to a halt in front of one stall.

I could see smoke rising from the clay burner in front of a mystical woman her as she mixed her potions. Later I met one of her patrons, Fouad, who explained that he was buying bakhor, a blend of ingredients including wood-chips, fragrant oils, sandalwood, cloves, sugar … and frankincense.

The bakhor-maker, Fatima, had learned her craft from her mother and grandmother who came from the south where the frankincense trees grow. She mixed the ingredients according to Fouad’s direction.

“More of this,” he’d say.

The bakhor’s aroma is released by the heat of the charcoal and this perfumes the entire home. At the stall next door there are pyramid-shaped stands which you can drape laundry over, so clothes too can be perfumed by the bakhor.

Omani men wear a tassle on the right side of their dishdasha (long, collarless dress) so they can keep their favourite scent close by. Whether you enter a hotel, a shop or even a car in Oman, the aroma of frankincense follows you.

After seeing wild frankincense trees at Wadi Dawkah, we watched clumps of dried resin being sorted and graded at Salalah’s Al Husn Souk.

Incense has been burned for millennia to freshen and ‘cleanse’ the environment. In the Omani home it’s as traditional as rose-water sprinklers, cardamon-scented coffee and dates.

One lovely custom from the 18th century, was that incense-burners would be carried through a home after the conclusion of the meal to signal it was time for guests to leave.

“I cannot live without this!” Exclaimed Fouad, the man I met at Muttrah Souk adding that he often swallows a tiny piece of frankincense if he’s feeling unwell.

As I turned to wave goodbye, Fouad was still inhaling bakhor, a look of deep satisfaction on his face.