Gifts From the Desert

The tour guide noticed that I applied cream to my psoriasis-affected fingers which were split and painful.

We were in southern Oman, travelling on the road to Yemen, an ancient caravan trade route still used to this day.

“You have a problem with your skin?” queried Quaid solemnly.

At the driving wheel, he was dressed in a turban, pristine Dishdasha and Ray Bans. As he glanced sideways, his expression softened. Within seconds, he was grinning.

“Do you want to try the local treatment?”

Having just told us a joke about desert camels being black because they don’t use sunscreen, I wasn’t sure how to take his offer.

“It will hurt the first few times,” he said. “But it will fix any skin issue. And it’s free.”

“Is it a tonic?” I asked, naively.

“Sort of. You can even mix it in milk and drink it.”

He assured me he wasn’t joking. And when you’ve tried pretty much every cure for split fingers, you tend to be up for the next miracle potion.

The cure, according to Quaid, is to use the urine of a virgin camel aged around 4 years old, applied to the affected area twice a day for at least three days.

I was game to try it, although I preferred application to the consumption method. But as he added more detail, it transpired that the urine wasn’t to be found in a small, clean bottle from a pharmacy or anything like that. You source it from a Bedouin farmer. I could see a problem continuing this treatment in the medium term, although as Quaid helpfully reminded me, we have camels in Australia too.

Thousands of camels roam the Southern Omani province of Dhofar. Despite appearances, they are not wild and have the right of way on highways.

Sometimes camels are passengers too.

Desert camels are either dark or light in colour, small with a small single hump (dromedaries rather than bactrian). They are farmed for milk, meat and their hides.

“It’s good for everyone to keep a few camels,” Quaid said. “Even in my family we have around ten or twenty camels.”

For his wedding recently, Quaid bought four camels for the buffet feast to feed 1,500 guests. It wasn’t enough. The meat ran out at 12.30 pm, which, for an all day event, was not ideal. Men don’t need invitations to turn up to a wedding, so estimating guest numbers are tricky. There is a separate event for men and women. To attend a woman’s wedding you need an invitation. In the past, the families spent days preparing for a wedding feast, but in modern times there are caterers. All the groom has to do is to provide the meat.

Our discussion took place in the Najid Desert, on the highway towards Yemen and our destination, the fabled sands of the Empty Quarter. This unforgiving terrain drew the great explorers of the past from Bertram Thomas, Wilfred Thesiger (AKA Mubarak Bin London) to Freya Stark.

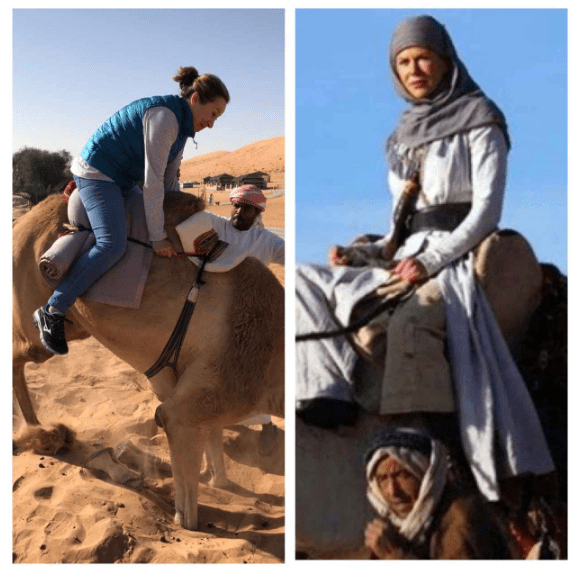

While the desert can conjur up images of romance, there is nothing romantic about travelling on a camel. My witty co-travellers pointed out that Nicole Kidman (playing the role of Gertrude Bell in the film ‘Queen of the Desert’) sat in front of the camel hump and appeared dignified and commanding, whereas I was instructed to sit behind the hump which was neither dignified nor commanding.

From two trips into the desert in the past ten days, my greatest fear was our 4WD slipping sideways down a dune. But our guide Quaid was right. The desert needs a kind of ’no surrender’ attitude.

“The secret of the desert is not to show fear.” he says

For travellers of the past, surrender meant certain death. Quaid has a point. Indecision combined with fine, ochre sand is a poor partnership.

But such thoughts were banished as a herd of camels came into view as we observed from the top of the dune. It was like being on the set of the remake of ’Lawrence of Arabia’, only the desert in front of us was not brown and oppressive. It was very green. Two cyclones in southern Oman last year saw parts of the Empty Quarter flooded. The desert hasn’t been this verdant in sixty years.

Later that day, we saw another herd of camels feeding between clumps of wild Frankincense trees. Southern Oman is one of the few places in the world where this special tree grows (more in another post). I wondered if I should approach the Bedouin farmer accompanying the camels about obtaining some medicinal camel urine. But Quaid had other ideas. At the foot of the Frankincense tree (which was not in a protected area, I hasten to add) someone who’d come before us had cut the bark and white sap was oozing onto the ground. the resin was still moist and pliant.

Quaid suggested I put a bit of the sticky resin on my split fingers.

“Maybe this will be simpler than the other cure. It’s like nature’s band-aid.”

I later discovered that camel urine (not necessarily from virgin camels) is widely believed to have healing powers. However scams have surfaced where unscrupulous vendors have used a urine source closer to home.

I still have split fingers. But they seem to work okay as I reminisce about those wonderful desert creatures that filled the imagination and delight of my fellow travellers on our Oman to Zanzibar adeventure. Now if I can just work out how to sit in front of the hump….